Barreiros - Madeira

1940 The Royal Ulsterman's first landfall was Porto Santo, an outer island of the archipelago and just out of sight of the main island. The weather was excellent as were the first impressions. On arrival, Funchal seemed like a pretty toy town with countless red-roofed houses on the base of a towering mountain half hidden by cloud. The first few days were spent at the Savoy, a rather posh hotel, followed by a move to Villa Begonia, in the outskirts of the town. It was an idyllic place with a lawn and a summerhouse in the garden.

1940 The Royal Ulsterman's first landfall was Porto Santo, an outer island of the archipelago and just out of sight of the main island. The weather was excellent as were the first impressions. On arrival, Funchal seemed like a pretty toy town with countless red-roofed houses on the base of a towering mountain half hidden by cloud. The first few days were spent at the Savoy, a rather posh hotel, followed by a move to Villa Begonia, in the outskirts of the town. It was an idyllic place with a lawn and a summerhouse in the garden.

The Savoy Hotel

The villa was shared with a family who owned a shop in Gibraltar just opposite Pepe's (1.1) called Wembley Stores. The Chipulina family also employed a young housemaid called Inez. Private tuition was soon arranged for Maruja but for the time being Eric was allowed to continue to enjoy his extended holiday.

Madeira was a volcanic island. Much of its coastline was either rocky or full of enormous boulders and swimming was mostly restricted to public bathing pools such as the Lido which was right by the sea and just down the road from the house. It was here that Eric contracted an ear infection that gave him a rough time while at Villa Begonia.

On closer inspection, however, Madeira was not quite the paradise it had appeared at first: at least not for everybody. Life in the rural areas was feudal and there was a ubiquitous and arrogant clergy. Some, judging by their fire and brimstone sermons, seemed obsessed with what they considered to be immodest feminine dress. There was local conscription, and the sight of the poor quintos with shorn heads looking like turnips, was pathetic. Their route marches were headed by a drummer or two with a bored looking officer on horseback in front. Wherever they went they left a mule-like stench behind them. The soldiers who manned the AA batteries had arrived from Lisbon. They looked like elite guardsmen by comparison.

Madeira was a volcanic island. Much of its coastline was either rocky or full of enormous boulders and swimming was mostly restricted to public bathing pools such as the Lido which was right by the sea and just down the road from the house. It was here that Eric contracted an ear infection that gave him a rough time while at Villa Begonia.

On closer inspection, however, Madeira was not quite the paradise it had appeared at first: at least not for everybody. Life in the rural areas was feudal and there was a ubiquitous and arrogant clergy. Some, judging by their fire and brimstone sermons, seemed obsessed with what they considered to be immodest feminine dress. There was local conscription, and the sight of the poor quintos with shorn heads looking like turnips, was pathetic. Their route marches were headed by a drummer or two with a bored looking officer on horseback in front. Wherever they went they left a mule-like stench behind them. The soldiers who manned the AA batteries had arrived from Lisbon. They looked like elite guardsmen by comparison.

My Brother Eric. This snapshot was taken in Madeira on the 24th of July 1940 very shortly after the family arrived. I think it was taken for passport or some other official reason.

The people of Funchal itself were a different story. They had been dealing with foreigners all their lives. Madeira, after all, had been a resort contemporary with the Riviera and San Sebastian. Even among the uneducated most of them knew what was what. In fact Madeira was basically a tourism orientated economy, and the advent of the 'Gibraltinos', as the evacuees were called, was a godsend to them, spending money and filling hotels which would otherwise have remained empty and closed because of the war.

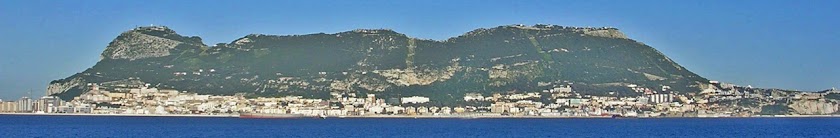

A view of Funchal from the Savoy Hotel

Generally the standard of living was so low that absolutely everything that could be used or consumed had a price. Anyone with a pen, a stamp or a watch was sitting pretty. Even such things as a vest, or a pair of socks could easily be flogged for American cigarettes to small time smugglers who obtained the fags from merchant ships in Port. American and British cigarettes were a luxury at the time and it was by no means a rare sight to see a posh looking gentleman strolling into a good tobacconist on the main avenue to buy a handful of British cigarettes with the air of someone selecting some choice Havana cigars. On the whole, that charming old Portuguese saying which defines human solidarity as, 'el que ten, ten, el que nao ten que se foda', was quite apposite for Madeira.

On the 24th of September Gibraltar suffered its fifth and longest air raid. It lasted two and a half hours. Two days later there was a further air raid carried out by over one hundred French aircraft. Several people were killed and there was considerable damage to private property.

On the 9th of October the British School for Gibraltar Children opened in Funchal. The Headmaster was a member of a local British family. The seventeen members of the teaching staff were all evacuees from the Rock. Among them were Elena Romero, Marilou Canessa, and others who were good family friends of the Chipulinas. Eric and Baba both went to this school during their stay in Madeira. Among the usual nonsensical rules demanded by most schools there was one which stated categorically that:

'English is the only language allowed to be spoken in the school. Those who speak Spanish may be punished.'

It was a rule that was flaunted from day one. For example most of the nonsense verses bandied about by the pupils were usually in Spanish. The following one was very popular.

'Enteramente en una olla,

Habian dos ajos y tres cebollas,

Catorce ojas de coliflor,

Remolacha y pepino y medio limón.

Y se pone al fuego y se tapa bien

Y se deja puesto hasta fin de mes.

Cuando se calcule que está bien cocido

Se le pone a fulano una papa en el ombligo’

The word fulano, of course, was usually substituted with the name of the person the children were making fun of.

On the 24th of September Gibraltar suffered its fifth and longest air raid. It lasted two and a half hours. Two days later there was a further air raid carried out by over one hundred French aircraft. Several people were killed and there was considerable damage to private property.

On the 9th of October the British School for Gibraltar Children opened in Funchal. The Headmaster was a member of a local British family. The seventeen members of the teaching staff were all evacuees from the Rock. Among them were Elena Romero, Marilou Canessa, and others who were good family friends of the Chipulinas. Eric and Baba both went to this school during their stay in Madeira. Among the usual nonsensical rules demanded by most schools there was one which stated categorically that:

'English is the only language allowed to be spoken in the school. Those who speak Spanish may be punished.'

It was a rule that was flaunted from day one. For example most of the nonsense verses bandied about by the pupils were usually in Spanish. The following one was very popular.

'Enteramente en una olla,

Habian dos ajos y tres cebollas,

Catorce ojas de coliflor,

Remolacha y pepino y medio limón.

Y se pone al fuego y se tapa bien

Y se deja puesto hasta fin de mes.

Cuando se calcule que está bien cocido

Se le pone a fulano una papa en el ombligo’

The word fulano, of course, was usually substituted with the name of the person the children were making fun of.

These carts drawn by bullocks were ubiquitous in Funchal. They had no wheels.

The family were still living in the Villa when Baba and Eric renewed their schooling. The authorities used a system of buses to get some of the children to school as the distances from the outskirts of the town to the school were substantial. As there was an acute shortage of text books at the time, the children were often required to copy their lessons from the few that were available. Both took their Cambridge GCE exams on the island. Baba was in fact a member of the first certificate class of the school to receive the awards. The certificates were ceremoniously delivered to them in front of the whole school.

The British School for Gibraltar Children in Funchal, Madeira. The first school certificate class receive their awards as the rest of the school looks on. I think there were nine students all told. Maruja is the one with the polka dot dress on the far right. This is one of two photographs of this event. The one shown here is from T.J. Finlayson’s book ‘The Fortress Came First'.

The exams were held in December in a large hall in the Golden Gate Hotel in the centre of town. They had to be written in pencil, with a carbon copy, a war time precaution in case the originals were lost. When Eric took his, the date coincided with an anniversary called Restauradores. This was a noisy commemoration of an important event in the history of Portugal and the unfortunate candidates were treated to a cacophony of drums and bugles just outside the place where the pupils were taking the exam. In the evening, students in traditional black capes would go round town scribbling on doorways the magic date when this event had taken place.

The family were still living in the villa when news arrived of the first blitz on British citizens. It was here also that they learned that Pepe (1.1) had contracted Hodgskin's disease, an illness they had never heard of before. He would require treatment in Lisbon. As he intended to convalesce in Funchal, the family decided to move to a house in an area called Barreiros. There was really not enough room in the Villa and in any case Pepe (1.2) wanted some privacy. Inez, the housemaid from Villa Begonia moved with them.

The family were still living in the villa when news arrived of the first blitz on British citizens. It was here also that they learned that Pepe (1.1) had contracted Hodgskin's disease, an illness they had never heard of before. He would require treatment in Lisbon. As he intended to convalesce in Funchal, the family decided to move to a house in an area called Barreiros. There was really not enough room in the Villa and in any case Pepe (1.2) wanted some privacy. Inez, the housemaid from Villa Begonia moved with them.

School Certificate class, The British School for Gibraltar Children, Funchal, Madeira. Maruja is on the right of the four girls. The girl on the left is Anita Alcantara, a good friend of Maruja who now lives in Madeira. This is an enlarged detail of the second photograph of which I have the original.

The house in Barreiros had a large balcony which faced a massive mountain range covered with rich sub-tropical vegetation, studded with toy-like, white-walled houses with traditional red-tiled roofs. It was an irresistible view for a landscape water-colour artist like Pepe (1.1). The ground floor of the house was a shop which was also a tavern of sorts. It was usually very busy as it was the only one in the vicinity.

Pepe's salary from the Manpower Office of 16 pounds a month must have been relatively good, as he was able to keep the family living comfortably there without Government assistance for some time. Maria Luisa (2.4), still as obstreperous as ever, insisted in talking to the Portuguese in Italian. Nevertheless she did seem to have a certain knack for languages. Eric had once been amazed to see her deep in conversation with some shipwrecked Lascars off a battered convoy as they walking about Funchal in their pyjamas. She must have been trying out the Urdu she learned during her days in Bombay. Perhaps it was even Hindi.

For the civilian population in Gibraltar, however, life must have been pretty grim. Friends tended to 'mess' together for convenience and although there was no blackout, the curfew was an uncomfortable imposition. There were A.A. guns, fortified points, pillboxes, barbed wire, and restricted areas at every turn. The remaining space was always jam-packed with servicemen, not just from the garrison, but with men from practically every nationality involved in the war. Main Street was one long file of bars and fruit shops and the smell of orange peel was endemic in cinemas and football grounds.

A useful safety valve was the fact that both the garrison and the civilians were allowed to cross into Spain. The brothels in La Linea must have worked non-union hours. It was about this time that the standard phrase used by servicemen approaching Spanish women at the frontier, known locally as 'Four Corners', was first coined: 'Llevo bolso. ¿Acompaño a Four Corners? '

One thousand miles to the north, events were gathering momentum and history seemed to be closing in on the Rock yet again. On the 23rd of October Hitler met Franco in Hendaye and tried to convince him to allow German troops to move through Spain to Gibraltar and thence to North Africa. He did not succeed. Franco must have laid on his Galician charm as Hitler is reputed to have said that he would prefer to have all his teeth pulled out than go through a meeting like that again.

Pepe's salary from the Manpower Office of 16 pounds a month must have been relatively good, as he was able to keep the family living comfortably there without Government assistance for some time. Maria Luisa (2.4), still as obstreperous as ever, insisted in talking to the Portuguese in Italian. Nevertheless she did seem to have a certain knack for languages. Eric had once been amazed to see her deep in conversation with some shipwrecked Lascars off a battered convoy as they walking about Funchal in their pyjamas. She must have been trying out the Urdu she learned during her days in Bombay. Perhaps it was even Hindi.

For the civilian population in Gibraltar, however, life must have been pretty grim. Friends tended to 'mess' together for convenience and although there was no blackout, the curfew was an uncomfortable imposition. There were A.A. guns, fortified points, pillboxes, barbed wire, and restricted areas at every turn. The remaining space was always jam-packed with servicemen, not just from the garrison, but with men from practically every nationality involved in the war. Main Street was one long file of bars and fruit shops and the smell of orange peel was endemic in cinemas and football grounds.

A useful safety valve was the fact that both the garrison and the civilians were allowed to cross into Spain. The brothels in La Linea must have worked non-union hours. It was about this time that the standard phrase used by servicemen approaching Spanish women at the frontier, known locally as 'Four Corners', was first coined: 'Llevo bolso. ¿Acompaño a Four Corners? '

One thousand miles to the north, events were gathering momentum and history seemed to be closing in on the Rock yet again. On the 23rd of October Hitler met Franco in Hendaye and tried to convince him to allow German troops to move through Spain to Gibraltar and thence to North Africa. He did not succeed. Franco must have laid on his Galician charm as Hitler is reputed to have said that he would prefer to have all his teeth pulled out than go through a meeting like that again.